“POLICY: Pet food consisting of material from diseased animals or animals which have died otherwise than by slaughter, which is in violation of §402(a)(5) will not ordinarily be actionable, if it is not otherwise in violation of the law. It will be considered fit for animal consumption.”

—FDA Compliance Manual: CPG § 690.300

(Canned Pet Food)

“Federal law (the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act) prohibits a euthanized animal to become food. However, the FDA doesn’t agree with federal law; the FDA stands in firm defiance of federal law through its “Compliance Policies.”

Some pet food is a dumping ground for “specified risk materials,” and situations for “diverted food” can include: pesticide or microbial contamination, contamination by industrial chemicals, natural toxicants, filth, or unpermitted drug residues..””

How Did We Get Here?

In a 2008 report following a 2-½ year study, the Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production (IFAP) described “an agro-industrial complex” beholden to the profit-making of the pharmaceutical lobby and the factory farming industry: manipulating control over regulatory agencies and Congress to support a system that “poses unacceptable risks to public health, the environment and the welfare of the (feed)

animals themselves.”

Aside from prohibitions regarding sale of certain narcotics (potentially addictive substances that blunt the senses), Federal regulatory control ensuring the safety of foods and new drugs in the consumer marketplace did not exist until 1938.

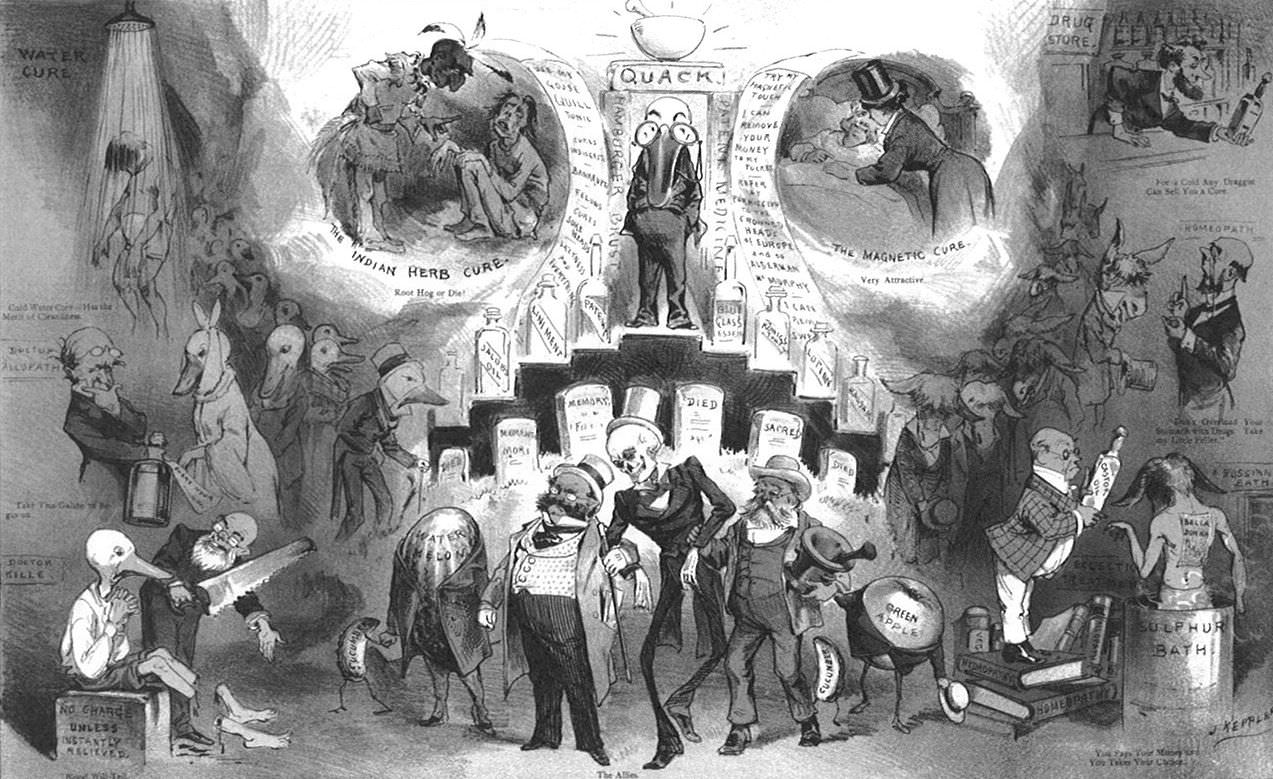

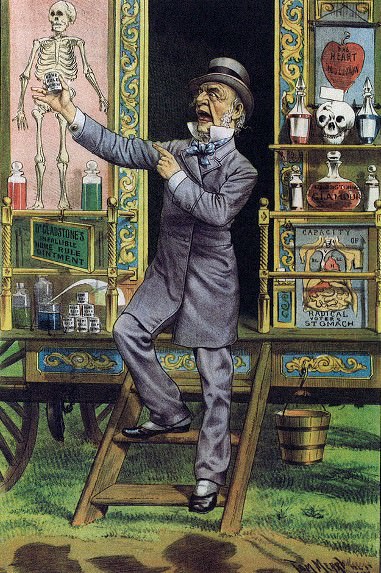

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 (PFDA), provided for federal inspection of meat products, and prohibited manufacture or transportation of poisonous patent medicines (ineffective, but heavily promoted “medical cures”) which often contained alcohol, morphine, cannabis, cocaine, and heroin as “secret ingredients.” The PFDA was the culmination of about 100 bills over a quarter-century that aimed to rein in long-standing, serious abuses in the consumer product marketplace. The intent behind PFDA was to protect the public against adulteration of food and from products marketed as healthful but

without scientific support.

Federal public health protection was vigorously advocated by Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley, who at the time was chief chemist of the Bureau of Chemistry of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, FDA’s predecessor. The 1906 Act was passed with his efforts and in response to the public outrage at the appallingly unhygienic conditions in the Chicago stockyards that were described in Upton Sinclair’s book “The Jungle.”

American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair published The Jungle in 1906, a socialist argument dramatized through a narrative that portrayed the hopeless, harsh conditions and exploited lives of immigrants in industrialized cities like Chicago. Readers, however, reacted more to Sinclair’s description of the unsanitary practices in the American meatpacking industry during the early 20th century, where the plot was set; with Sinclair himself observing: “I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

Debate about these issues led to creation of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which today holds responsibility for testing/ensuring safety of all foods and drugs destined for human (and animal) consumption.

“All day long the blazing midsummer sun beat down upon that square mile of abominations...””

...upon tens of thousands of cattle crowded into pens whose wooden floors stank and steamed contagion; upon bare, blistering, cinder-strewn railroad tracks and huge blocks of dingy meat factories, whose labyrinthine passages defied a breath of fresh air to penetrate them; and there are not merely rivers of hot blood and carloads of moist flesh, and rendering-vats and soup cauldrons, glue-factories and fertilizer tanks, that smelt like the craters of hell—there are also tons of garbage festering in the sun, and the greasy laundry of the workers hung out to dry and dining rooms littered with food black with flies, and toilet rooms that are open sewers...

“Relentless, remorseless, it was; all his protests, his screams, were nothing to it - it did its cruel will with him, as if his wishes, his feelings, had simply no existence at all; it cut his throat and watched him gasp out his life...””

Continuing a tradition of investigative journalism, reform-oriented correspondents known as muckrakers[1] emerged in the US shortly after 1900. Published competitively in popular magazines, these writers heightened public awareness of safety issues stemming from careless food preparation procedures and the increasing incidence of drug addiction from patent medicines (both accidental and intentional). Dr. Wiley lent scientific support, publishing his findings on the widespread use of unsafe preservatives in the meat-packing industry.

Among the scandals, the US Army had contracted with 3 Chicago producers for shipment of low-cost canned beef to American soldiers in Cuba during the Spanish-American War (1898). Taking advantage of the military’s inattentiveness and favorable regard to the industry, the vendors shipped meat packed in tins along with a visible layer of boric acid, which was thought to act as a preservative and was used to mask the stench of the rotten meat. In 1899, Thomas F. Dolan, a former superintendent for Armour & Co., one of the packers, signed an affidavit noting the ineffectiveness of government inspectors and stating that the company’s common practice was to pack and sell “carrion” (dictionary definition: “rubbish/refuse/garbage”), the toxic beef reviving the Civil War term: “embalmed beef.”

Troops became unfit for combat, as the meat led to widespread illness and death from dysentery and food poisoning, being particularly deadly to thousands already weakened by epidemics of malaria and yellow fever and wreaking havoc on the unprotected American troops, (eventually killing twice as many men as from combat).

Since yellow fever frequently manifests symptoms similar to bacterial food poisoning, only modest connection was made at the time between illness and consumption of the Chicago beef.

Immediately preceded by The Meat Inspection Act of 1906—(prohibiting the sale of adulterated or misbranded livestock and derived products as food and requiring that livestock were slaughtered and processed under sanitary conditions)—the PFDA was vigorously opposed by well-funded lobbyists representing the “Beef Trust” (a collaborative group made up of the five largest meatpacking companies, and its base of packinghouses in Chicago’s Packingtown area) and drug manufacturers, and challenged as constitutionally unsound by numerous Southern senators.

The vigorous involvement of Theodore Roosevelt, who had condemned Sinclair but became disturbed after reading Sinclair's novel—and tasting some of the meathimself—prevailed over Congressional reluctance. Roosevelt threatened to publish an independent investigation by labor commissioner Charles P. Neill and social worker James Bronson Reynolds that confirmed Sinclair’s depiction of the packinghouses.

The PFDA was to be applied to goods shipped in foreign or interstate commerce, and implemented by the US Department of Agriculture Bureau of Chemistry. Food was defined as adulterated if it contained “filthy” or decomposed animal matter, poisonous ingredients, or additives that attempted to conceal inferior ingredients. More accurate labeling of these products pursuant to the Act (prohibiting false claims about strength and purity, and, a decade later, a requirement for packaged goods to designate accurate weight) caused sales of adulterated or misbranded drugs to swiftly decline since they could not gain government certification.

The Federal Trade Commission was given responsibility for the advertising portion (the Wheeler-Lee Act: “unfair or deceptive acts or practices” and also “unfair methods of competition”) and the Bureau of Chemistry for the “misbranding” issues.

After the Spanish-American War, Spain ceded the Philippines to the US pursuant to the Treaty of Paris (30 Stat. 1754), and recognizing the growing social problem of opium addiction in the Philippines and the states, the Brent Commission (Charles Henry Brent: an American Episcopal bishop who served as Missionary Bishop of the Philippines beginning in 1901) recommended that narcotics should be subject to international (licensing) control.[2] In 1914, at the urging of NY Representative Francis Burton Harrison, Congress implemented the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act (Ch. 1, 38 Stat. 785) regulating and taxing production, importation, and distribution of opiates.

Although initially aggressive, the USDA Bureau of Chemistry's authority was impeded by judicial decisions, which narrowly defined the agency’s powers and set high standards for proof of fraudulent intent. In 1927, the Bureau’s regulatory authority was re-organized under a new USDA body, The Food, Drug, and Insecticide Administration; shortened to Food and Drug Administration (FDA)three years later.

Government fails its citizens:

the FDA in “Regulatory Capture”

In the mid-1930s a growing consumer movement began to emerge, amid criticism of the perceived inadequacy of the FDA to protect the public from being victimized by increasingly aggressive professional promotional campaigns for dubious “wonder drugs,” untested cosmetics, and mis-labeled or adulterated foodstuffs.

Numerous muckraking press articles and books including “100,000,000 Guinea Pigs: Dangers in Everyday Foods, Drugs, and Cosmetics” (Arthur Kallet and F.J Schlink; 1933) postured that the FDA was held in “regulatory capture”: created as a state regulatory agency to act in the public interest, but instead advancing commercial or special interests that dominated the industries it was charged with regulating. As a “failure of government,” regulatory capture ultimately encourages a business model wherein large firms impart negative economic and moral social costs on consumers (the third party in the relationship). Examples of these negative externalities are the environmental consequences of production and use of unregulated goods; and the unknown side effects of mis-labeled pharmaceuticals and cosmetics on buyers.

At the same time, FDA officials had assembled a collection of problem products, eventually dubbed “The American Chamber of Horrors,” to expose the legal weaknesses in the 1906 Act that frustrated government enforcement efforts.

Many cosmetics at that time were formulated with lead, arsenic, or radium; of which consumers had no understanding of the health effects: Kallet and Schlink argued that many of these products could not be sold if they were properly labeled. They warned that consumers were “guinea pigs” in long-term poisoning experiments, most particularly ignorant of the danger for multiple low concentration toxins to synergize (combine and interact), which might be even more harmful that each substance would be individually. Calling for sturdier penalties against offending companies, the authors admonished: “let your voice be heard loudly… in protest against indifference, ignorance, and avarice responsible for the uncontrolled adulteration and misrepresentation of foods,

drugs, and cosmetics.”

The inadequacy of The Pure Food and Drug Act emerged as a national concern. Amid this heated environment, the catalyst for change was the “Elixer Sulfanilamide” Poisoning Crisis in 1937, wherein more than 100 people in 15 states died after ingesting a sulfanilamide medication intended to treat streptococcal infections. Used for some time in tablet and powder forms, the marketing division of Bristol, TN pharmaceutical company S.E. Massengill attempted to respond to consumer demand for a liquid formulation. A vehicle for the drug was problematic, and, experimenting for a solvent, Harold Watkins, the firm’s chief chemist found that sulfanilamide would dissolve in diethylene glycol (DEG).[3]

DEG is a colorless, nearly odorless, and hygroscopic (absorbs moisture from the air) liquid with a sweet-ish taste. It is miscible (it will mix regardless of proportions) in water, alcohol, ether, acetone, and ethylene glycol. Today, DEG is a widely used solvent in the manufacture of unsaturated polyester resins, polyurethanes, and plasticizers. Massengill employees were apparently unaware that two previous studies reported that DEG was toxic. There were no regulations requiring premarket safety testing of new drugs... and so, adding raspberry flavoring, the company control lab merely tested the mixture for taste, appearance, and fragrance; and shipped it

across the country.

Within a month, the American Medical Association received reports of kidney failure and deaths from the medication, and soon after, FDA identified DEG as causal. Massengill, however, was dismissive of criticism: insisting that they had only supplied a “legitimate professional demand” for a curative product and held no legal responsibility to anticipate the tragedy.

In fact, there was no requirement for demonstrating that new medicines were safe; only that they be labeled accurately: the FDA had no authority to reprimand the company. The firm paid a minimal fine under stipulations of the previous 1906 PFDA, which prohibited labeling the preparation an “elixir” if it had no alcohol in it. Still, with his trial pending two years later, Watkins took his own life.

Pressed by public outcry, Congress replaced the PFDA with the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act in 1938 (FFD&C Act: P.L. 75-717; 52 US Stat. 1040; 21 USC § 301 et seq), imparting authority to oversee safety of food, drugs, and cosmetics to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). By this authority, FDA “administers” the Act. The FFD&C Act required companies to perform animal safety tests on proposed new drugs and submit the data to the FDA before being allowed to market their products. The FFD&C Act now prohibited false therapeutic claims, and mandated a list of “active ingredients”[4] on the label as well as directions for use.

In 1968, the FDA formed the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI), incorporating recommendations from a National Academy of Sciences investigation into FFD&C Act, in order to classify all pre-1962 drugs that were already on the market as either effective, ineffective, or needing further study (the Kefauver-Harris Amendment). By 1981, FDA had taken action on 90% of all DESI products.

The FFD&C Act has been amended many times, most recently to add requirements about preparation for bioterrorism (HR 3850, The FDA Amendment Act of 2007: FDAAA). FDAAA broadened FDA authority to investigate pediatric applications of medical products, and sought to improve funding of the FDA through increased drug review submission fees including those for direct-to-consumer advertising. The FDAAA fortified limitations on the conflicts of interest that are permitted in the advisory committees responsible for drug application approval, and established a non-profit institute to encourage investigation of improved methods of product safety evaluation. Notable for this essay is that the FDAAA created a registry of contaminated food and a searchable public database of clinical trial data.[5]

The FDA moves to weaken Federal food safety law.

How FDA

defines "Adulteration" of pet foods

The FFD&C Act expressly enfolds protection of pet foods and animal “feeds” used for livestock. The FFD&C Act requires that pet foods be clean (uncontaminated) and generally nourishing, contain no harmful or toxic/lethal substances, and be accurately (truthfully) labeled.

The FFDCA defines a food as “adulterated” (impure) if it contains harmful or poisonous substances which may cause injury to health; if it has been prepared, packed, or stored under unsanitary conditions through which it may have been contaminated with soil or debris or rendered injurious to health; if it contains any part or product of a diseased animal; or, if its container is composed of any poisonous or harmful material which may render the contents injurious to health. Food may also be adulterated if any important ingredient has been omitted or substituted.

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

• 21 USC Ch. II, § 321 (f) defines food: “The term ‘food’ means (1) articles used for food or drink for man or other animals, (2) chewing gum, and (3) articles used for components of any such article.”

• 21 USC Ch. 9 § 342 defines Adulterated food: “A food shall be deemed to be adulterated if it contains (a)(1) Poisonous or deleterious substance”; or (a)(1)(3) “if it consists in whole or in part of any filthy, putrid, or decomposed substance”; or (a)(1)(5) “if it is, in whole or in part, the product of a diseased animal or of an animal which has died otherwise than by slaughter;”

An “animal which has died otherwise than by slaughter” is one be one that had died in a stall where it was raised or “in the field” (one that died despite efforts to drive it to the slaughterhouse: so called “downer” cattle”[6]), or one that had been euthanized. Presumably, this would also preclude sodium pentobarbital, the drug used to euthanize.

Another term used to describe these animals is “4D”: dead, dying, disabled, or diseased.

but

what are

fda

compliance policies?

FDA instructs its field representatives to overlook federal law

The FFD&C Act, as federal law, makes clear that no human or pet food is permitted to contain a poisonous, insanitary, deleterious ingredient or is sourced from a diseased animal or animal that has died other than by slaughter. FDA is charged with authority for administration and enforcement of that law. However, though its own “Compliance Policies,” the FDA instructs its Field Representatives to overlook the Federal law. As a result, pet food manufacturers have been given leeway to

violate Federal law.

The published guides are intended, according to the FDA, to “advise FDA's field inspection and compliance staffs, as well as the industry, as to the Agency's strategy and policies to be applied when determining industry compliance.”

CPG (Compliance Policy Guide)

§ 675.400 Rendered Animal Feed Ingredients

“POLICY:

No regulatory action will be considered for animal feed ingredients resulting from the ordinary rendering process of industry, including those using animals which have died otherwise than by slaughter, provided they are not otherwise in violation of the law.”

Rendering[7] is the process of boiling and separating fat that converts dead animals and animal parts that otherwise would be discarded (garbage) into a variety of materials, including edible and inedible tallow and lard and proteins such as meat and bone meal (MBM); (read more here). The US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) specifically cautions that consumption of euthanized animals can lead to death (“Secondary pentobarbital poisoning” ) and suggests the possibility of civil liability pursuant to state and local laws.

FWS disagrees with FDA tolerance of rendering euthanized animals— animals that have died otherwise than by slaughter— into pet /animal food: “Rendering is not an acceptable way to dispose of a pentobarbital-tainted carcass. The drug residues are not destroyed in the rendering process, so the tissues and by-products may contain poison and must not be used for animal feed.” (CLICK HERE to read the FWS Report).

CPG § 690.500 Uncooked Meat for Animal Food

“BACKGROUND:

*CVM is aware of the sale of dead, dying, disabled, or diseased (4-D) animals to salvagers for use as animal food. Meat from these carcasses is boned and the meat is packaged or frozen without heat processing. The raw, frozen meat is shipped for use by several industries, including pet food manufacturers, zoos, greyhound kennels, and mink ranches. This meat may present a potential health hazard to the animals that consume it and to the people who handle it.*

POLICY*

Uncooked meat derived from 4-D animals is adulterated under Section 402(a)(5) of the Act, and its shipment in interstate commerce for animal food use is subject to appropriate regulatory action.*

REGULATORY ACTION GUIDANCE

*Districts should conduct preliminary investigations only as follow-up to complaints or reports of injuries and should contact CVM before expending substantial resources. Before the districts recommend regulatory action, they should contact Case Guidance Branch, HFV-236, for advice and assistance with case development.*”

Although the FDA acknowledges that such “meat” is adulterated pursuant to definitions of the FFD&C Act—and that, as the agency responsible for administering this federal law it has a duty to do so—FDA inspectors are forbidden to investigate or intervene unless related to reports of “injuries,” and even if so, must consult with its Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) before spending the money to scrutinize.

(Censored photo of rotting “offal”)

raw materials and by-products waiting for "rendering" into pet foods behind this blackout

CPG § 675.100 Diversion of Contaminated Food

for Animal Use

“BACKGROUND:

FDA does not object to the diversion to animal feed of human food adulterated with rodent, roach, or bird excreta. However, since rodent, roach, or bird excreta are vectors for microorganisms deleterious to the health of animals, including such things as parasite eggs, salmonella, leptospira, or other pathogenic organisms, diversion has not been authorized except following a heat treatment appropriate to destroy such organisms.

POLICY:

Diversion of rodent, roach, or bird contaminated food for animal feed use, whether pursuant to a court order or a voluntary action, requires heat treatment to destroy pathogenic organisms. The *Center for* Veterinary Medicine (HFV-236) should be contacted on a case-by-case basis concerning suitability of proposed treatment, whether pursuant to a court order or a voluntary action.”

CPG § 675.200 Diversion of Adulterated Food to Acceptable Animal Feed Use; Diversion of rodent, roach, or bird contaminated food for animal use

“BACKGROUND:

In the past, FDA has authorized the salvage of human or animal food considered to be adulterated for its intended use by diverting that food to an acceptable animal feed use. Most of these instances have involved, but have not been limited to, the interpretation of section 402(a)(3) and (4) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to allow different standards for foods intended for human use vs. food intended for animal use, e.g., defect action levels for filth in a food intended for human use but not for the same food intended for animal feed use.

Diversion requests, however, have also included USDA detained meat and poultry products contaminated with drug or other chemical residues, as well as food and feed under voluntary industry recall or quarantine that may be considered adulterated for their intended use(s).

To assist in handling certain specific types of diversion requests, the Agency has developed Compliance Policy Guide 7126.05. [Diversion (after heat treatment) of rodent, roach, or bird contaminated food for animal use.] No single set of criteria, however, can be prepared to cover diversion requests in all possible situations. This guide provides procedures for submitting requests to the agency for authorization to divert adulterated foods for which no criteria have been established.”

FDA re-defines “Filth”

So… the FDA has decided that despite Federal legal definitions, the word “filth” can mean different things… depending on who the manufacturer intends the product to be eaten by. CPG

§ 675.200 continues at length, describing the process to transmit requests for “diversion” which include:

“…k. The intended use of the diverted food. This will include complete description of the class of animals involved, whether they are food or non-food producing, the part of the country in which the food will be used, and all assurances that have been secured that indeed the food will be used as agreed.

m. Information from the firm proposing the diversion, sufficient for a determination whether disposition of such article, including packaging material, will result in the release of a toxic substance into the environment. [See 21 CFR 25.1(f)(9) and (g) and proposed 21 CFR 25.24(d)(4). An Environmental Impact Analysis Report under 21 CFR 25.1(j) or an Environmental Assessment under proposed 21 CFR 25.31 (44 FR 71747) is required if the proposed disposition fails to meet the above criterion for exclusion].

POLICY:

Diversion requests will be handled on an ad hoc basis. The *Center* will consider the requests for diversion of food considered adulterated for human use in all situations where the diverted food will be acceptable for its intended animal food use. Such situations may include:

a. Pesticide contamination in excess of the permitted tolerance or action level.

b. Pesticide contamination where the pesticide involved is unapproved for use on a food or feed commodity.

c. Contamination by industrial chemicals.

d. Contamination by natural toxicants.

e. Contamination by filth.

f. Microbiological contamination.

g. Over tolerance or unpermitted drug residues.

fda re-defines "diversion" and "adulteration"

so that waste can be used

in pet foods

Not what you'd think...

CPG § 675.200:

Some general policy issues to be considered while evaluating proposals for diversion of food considered to be adulterated to

animal feed use are:

a. A seizure action and a voluntary request for diversion are two separate processes. A seizure action and a request for diversion cannot legally be processed simultaneously. No diversion request submitted under this guideline will be considered once a seizure recommendation has been forwarded to headquarters. If a seizure recommendation is withdrawn and if the requirements of this policy are met, a diversion request may be entertained. Naturally, a diversion-based means of reconditioning seized articles may be an appropriate means of meeting the requirements of a court-ordered consent decree arising from a seizure.

b. Diversion may only be allowed where there is a legally enforceable assurance that the subject foods will not be placed into interstate commerce before the request is approved and the products appropriately diverted (i.e., meats not under USDA detention but nevertheless containing illegal residues would be appropriate for seizure or state embargo but not for diversion if the meats were already shipped in interstate commerce). Accordingly, this policy will primarily apply to embargoed goods or bonded goods to assure adequate control of the adulterated goods.

c. Where diversion is legally appropriate, data are required to demonstrate that the diverted use poses no safety hazards to the animals consuming the diverted food and to the public who may be exposed to edible tissues of such animals.

d. The diversion policy does not sanction or authorize the blending of the adulterated foods, i.e., the policy does not authorize the diluting of an adulterated product to below a tolerance or action level.

Although the FDA holds no authority to mitigate enforcement of the Act, the agency does so for animal feeds and pet foods:

FDA Compliance Policies impart pet food manufacturers

privilege to circumvent

Federal food safety laws.

This FDA Compliance Policy extends across the range of pet food ingredients… even vegetables, as an example. A pet food package designed with a tumbling rainfall of images of “wholesome ingredients” is a marketing tack, but doesn’t caution the consumer that it may portray neither the true quantity or quality of the vegetables or grains used in the pet food; which could be contaminated with pesticides, industrial chemicals, toxicants, “filth,” (examples: rodent, roach, or avian excrement) or other noxious microbiological contaminants. Remember that the FFD&C Act categorizes contaminated foods as "adulterated" (including those for pet foods) and prohibits their entry

to the marketplace.

Diverting rodent, roach or bird feces contaminated ingredients to use in pet foods

CPG § 555.650 Reconditioning Foods by Diversion for Animal Feed

POLICY:

Food Contaminated with Rodent, Roach or Bird Excreta

The diversion of such contaminated foods for animal feed purposes will be considered adequate.

REMARKS: The Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition *(HFS-605)* defers to CVM in questions concerning suitability of treatment proposed for reconditioning under the conditions specified in *Sec. 675.100* (CPG 7126.05).

FDA decides that Federal law…

is NOT “the law.”

According to the FDA, Compliance Policy Guides (CPG) explain FDA policy on regulatory issues for pet food manufacturers. These include Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) regulations and application commitments. CPGs advise FDA field inspection and compliance staffs as to the Agency's standards and procedures to be applied when determining industry compliance with Federal law.

Theoretically, CPG opinions may derive from:

a request for an advisory opinion;

from a petition from outside the Agency; or

from a perceived need for a policy clarification by FDA personnel.

The FDA held in

"Regulatory Capture"

FDA Compliance policies above are in direct violation of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act law. 21 USC Ch. II, § 321 (f) specifically includes food for animals within the scope of FFD&C Act regulation, and established a model to cover the range of horrific diversions into pet food. But in CPG 675.200, the FDA makes its own clarification: “No single set of criteria, however, can be prepared... in all possible situations.” Unilaterally, the FDA has re-defined administration of federal law.

Food Safety Critics suggest that the FDA, effectively in a modern form of “regulatory capture,” assumes a role as an archetype of deference to American capitalism. Called by many names (including those invented by the AAFCO to deflect notice by the consumer), ingredients that should be discarded or destroyed as waste can be legally diverted into pet food, supporting monolithic agribusiness profit models that turn garbage into profit.

That these profits exist at the possible health—or life—of an animal is inconsequential. It may be illegal under the law, but owing to FDA compliance policies, ingredients and foods that could include pesticide contamination, contamination by industrial chemicals, contamination by natural (or synthetic) toxicants, contamination by “filth, ” microbiological contamination, and/or dead, dying, disabled, or diseased (4-D) animals (“specified risk materials”) can be (and are) packaged, labeled, and sold as Premium Pet Food absent consumer awareness; but moreover, without any ability of the consumer to obtain information about such ingredients at all (protected as industry trade secrets).

This is a long way from the FDA's “American Chamber of Horrors” in the 1930s, as the regulatory agency, created to act in the public interest, instead now advances the commercial and political concerns of special interest groups like the Pet Food Institute (and AAFCO) that dominate the industry it is charged with regulating. When regulatory capture occurs, the interests of businesses or political action groups are prioritized over the interests of the public: leading to a net loss for society.

American pet food consumers mistakenly assume the products they feed their pets are produced under strict government scrutiny. The Pet Food Institute (PFI) propagandizes that “In the United States, pet food is among the most highly regulated of all food products,” and describes involvement of several federal and state agencies. The Institute is the lobbying group that drives the interests of the pet food manufacturing industry in Washington DC, as an “advocate for a transparent, science-based regulatory environment for our members.” Funded by 98% of US pet food manufacturers—including brokers, suppliers, and businesses that have become notorious for egregious behavior toward consumers and government regulators—PFI can outspend the FDA at any time, and works to ensure that federal or state legislation that would impose more concentrated supervision on the industry does not pass: providing for “consumer choice.”

The FDA instead is complicit with PFI in a process wherein pet food ingredients that can contain rendered laboratory animals, deceased zoo animals, “road kill,” or many other ghastly situations represented by vague umbrella terms as “animal fat,” “by-product meal,” “meat and bone meal,” “meat meal,” and “animal digest” (fat sprayed on dry “kibble” to make a dog eat an unpalatable product).

PFI aggressively drives industry agenda in absurdly non-objective and slickly scripted publicity materials which describe a “culture of safety” which enfolds a fantasy scenario that has proven to be systematically defied or ordinarily has failed on every level:

“Reliable and trusted ingredient suppliers;

Hygienic and secure design of pet food and treat manufacturing facilities;

Inspecting and testing ingredients during arrival and unloading;

Continuous monitoring during manufacturing;

Safety and traceability assurances during packaging; and

Regulatory oversight.”

The connection between

"Animal Fat"

and Pentobarbital

In 2002, the Congressional Research Service (Library of US Congress) issued its report, Animal Rendering: Economics and Policy, describing that “renderers annually convert 47 billion pounds of animal materials” and listed those sources: “meat slaughtering and processing plants, dead animals from farms, ranches, feedlots, marketing barns, animal shelters, and other facilities” (i.e., zoos, roadkill retrieved by local animal control officers or at municipal dumps, etc.), as well as “… fats, grease and other food waste from restaurants and stores.”

The FDA's Center for Veterinarian Medicine (CVM) undertook the project because veterinarians had complained that sodium pentobarbital, a short-acting barbiturate used as an anticonvulsant and surgical sedative, was losing its effectiveness; and theorized that dogs were somehow being chronically exposed to low levels (through dog food) which would make them resistant to its effects.

FDA conducted tests on dry commercial foods in 1998, and again in 2000. The first series of tests detected the presence of pentobarbital but did not indicate the levels that were present in the foods, neither of dog or cat DNA; declaring “the pentobarbital residues are entering pet food from euthanized, rendered cattle and even horses.”

The second tests were published in the American Journal of Veterinary Research in 2002. While 53% percent of the formulas from which results could be determined contained pentobarbital, the report contradicted the previous findings: “None of the 31 dog food sample examined in our study tested positive for equine-derived proteins.” Additionally, FDA stated: “Cattle are only occasionally euthanized with pentobarbital, and thus are not considered a likely source of pentobarbital in dog food.” The agency ended the report with the odd deduction: “Although the results of our study narrow the search for the source of pentobarbital, it does not define the source (ie. species) responsible for the contamination.” As a follow up to this study, the FDA performed sodium pentobarbital tests on Beagle subjects focused on a specific liver enzyme. The FDA acknowledges that they do not really know what possible impact the pentobarbital may have at the levels found in the study... yet they have concluded they are “probably” safe.

Biologically, the FDA has determined that the conventional pet food ingredient “Animal Fat” to be most likely to contain a euthanizing drug, (and thus most likely to originate from a euthanized animal). According to a 2002 FDA report Risk from Pentobarbital in Dog Food, because in addition to producing anesthesia, pentobarbital is routinely used to euthanize animals, the most likely way it could get into dog food would be in rendered animal products from shelters, veterinary clinics, or zoos (because of the cost: pentobarbital would never be used in livestock).

Among many chemical contaminants, pentobarbital seems to be able to survive the rendering process. Researchers from the University of MN followed a group of euthanized animals through a commercial rendering facility and determined that pentobarbital survived rendering without undergoing degradation: (1985) “The pentobarbital was distributed approximately equally between the meat and bone meal and tallow fractions.”[8]

If animals are euthanized with pentobarbital and subsequently rendered, pentobarbital could be present in the feed ingredients. In Buyer Beware: The Crimes, Lies and Truth About Pet Food (“How Horrible Can Pet Food Ingredients Get?”) Pet Food Safety Advocate Susan Thixton discusses that, as an un-named ingredient, there is no FDA information about what type of euthanized animal could be in “animal fat,” and as such, nor what other drugs could be potentially present.[9]

There is no CVM information on the health condition of animals used in these rendered (recycled garbage) pet food ingredients, nor data to help understand the health risk to household pets. In her book, Thixton ruefully observes that “dead animals from animal shelters are cooked (rendered) and turned into pet food and crayons” and that despite the report, “not one Representative of Congress did a thing about it.”

Within the EPA document “Emissions Factors and Policy Applications Center, Chapter 9: Food and Agricultural Industries, Section 9.5 Introduction to Animal & Meat Products Preparation” (§ 9.5.3 Meat Rendering Plants) appears confirmation that dogs and cats are indeed rendered into pet foods: “Independent plants obtain animal by-product materials, including grease, blood, feathers, offal, and entire animal carcasses, from the following sources: butcher shops, supermarkets, restaurants, fast-food chains, poultry processors, slaughterhouses, farms, ranches, feedlots, and animal shelters.”

Despite industry and government assurances, with four recalls over a recent two-year period, questions remain about how pentobarbital keeps ending up in pet foods. While illegal for pet food to be made of animal meat that isn’t explicitly killed for food, through its compliance policies FDA permits such meat to be used, so long as it doesn’t violate other regulations and is “decontaminated.” However, pet food is explicitly prohibited from containing pentobarbital-tainted meat. In 2002, FDA researchers postured that the contamination had mostly come from cattle; however, the agency cautions that there’s little use in extrapolating any of their results to the present day: “The sampling method and the age of the data generated by the survey means that the data cannot be used to draw inferences about dog food being produced and sold in the U.S. today.” This may be largely owe to the reality that the paradigm for pet food manufacture has changed dramatically since that time: since contract manufacturing (“co-packing”) is the norm, and malicious fraud (economically motivated adulteration) is more common.

Current “Good Manufacturing Practice

and Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Food for Animals”

The FDA Food Safety Modernization Act of 2010 (FSMA: January, 2011) is intended to ensure safety of the U.S. food supply by shifting the focus of federal regulators from responding to contamination to preventing it.

Ever-frequent and increasing reported incidents of food-borne illnesses between 2000 – 2010 provoked Congress to alarm. Fraud within ingredient sourcing became common to the extent that the term “economically adulterated ingredients” came into use. The FSMA imparts new authority and responsibility to the FDA to regulate how foodstuffs are grown, harvested and processed: FDA will have a legislative mandate to require comprehensive, science-based preventive controls across the food supply, including pet food and animal feed.

The FSMA represents the first time Food Defense (protection of food products from intentional contamination or adulteration by biological, chemical, physical, or radiological agents) has been incorporated into law. The Act will enfold protocols for inspection and compliance, response to contaminants/violations, suspension of manufacturer registration, and enhanced product tracing abilities.

Among these new powers, the Act grants the FDA mandatory recall authority, with the expectation of improved responsiveness and consumer confidence. As part of the process, the FSMA requires FDA to undertake at least a dozen rulemakings; publicize standards, and issue guidance documents for “Good Manufacturing Practice(s).” The FDA has failed to meet the ordered timetable for issuing regulations within 18 months: rules to protect against the intentional adulteration of food, including the establishment of science-based mitigation strategies to prepare and protect the food supply chain at specific vulnerable points.

Hazard Analysis and Risk-based Preventive Controls (HARPC) is a successor to the (1960s) Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) food safety system. All food companies in the United States that are required to register with the FDA under the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002, as well as firms outside the US that export food to the US, must have a HARPC plan in place within 36 months of the publication of the rules. HARPC focuses on “preventive controls” systems which emphasize prevention of hazards before they occur rather than their

detection afterwards.

Food safety advocates are critical that despite public posturing, the FDA, through its compliance policies, has (despite its federal mandate,) unilaterally decided that human and animal food will continue to be addressed through separate regulations and protection (§ 507.1(d)) Most offensively, is the FDA proposal for allowance of adulterated animal food, raw materials, and ingredients, including rework susceptible to contamination with pests, objectionable microorganisms, or unrelated materials in animal food if “a manufacturer wishes to use such materials in manufacturing such food.” According to:

21 CFR § 507.22 - Equipment and utensils.

(9) Adulterated animal food, raw materials, and ingredients must be disposed of in a manner that protects against the contamination of other animal food or, if the adulterated animal food, raw materials, or ingredients are capable of being reconditioned, they must be reconditioned using a method that has been proven to be effective;

Who Cares What it Looks like?

“...the Center for Veterinary Medicine does not believe

that Congress intended the Act

to preclude application

of different standards

to human and animal foods...”

FDA re-defines “Aesthetics”

Despite that the FFD&C Act clearly defines food as “for humans and animals” (21 USC Ch. II, § 321) and which thereby includes pet foods and pet treats, FDA Compliance Policies impart different standards to human and animal foods: “Different standards have historically existed for human and animal food concerned with aesthetics.” (GPC § 675.400).

Further in this section, the FDA considers insect or rodent contaminated pet food ingredients and diseased or euthanized animals to be merely of “aesthetic” consequence to pet food. And as such, by defining these rendered ingredients and other “contaminations” as aesthetic variables, the FDA condones violation of Federal law defining “adulteration” of ingredients: “Pet Food,” Author Thixton admonishes, “is the only industry in the US legally allowed to lie to consumers”:

CPG § 675.400 - FDA Compliance Policy on Rendered Animal Feed Ingredients

(BACKGROUND): “...the Center for Veterinary Medicine does not believe that Congress intended the Act to preclude application of different standards to human and animal foods under Section 402.

Different standards have historically existed for human and animal food concerned with aesthetics. The Center has permitted other aesthetic variables in dealing with animal feed, as for instance the use of properly treated insect or rodent contaminated food

for animal feed.”

FDA Now Says:

Pet Foods Can Be Drugs

The legal distinction between food and drug is key in terms of FDA's regulatory authority. The legal definitions of “food” and “drug” are very different, but become mingled when a food label bears a claim that consumption of the product will treat, prevent, or otherwise affect a disease or condition, or, to affect the constitution or function of the body in a way separate from what would ordinarily be described as from its “nutritive value.”

By definition, food is not a drug. Such claims effectively establish intent to proffer the product as a drug: “articles intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease in man or other animals” (FD&C Act 201(g) & (p) [21 USC 321(g) & (p)]).

In this instance, since the product would not have been subject to the normal premarket clearance mechanism to demonstrate safety and efficacy—as required for drugs—it is unsafe by definition. As such, dog food products with labels bearing drug claims are subject to regulation by FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) as drugs as well as foods. A manufacturer must then remove these claims to restore its regulatory status to only food.

The process for FDA drug approval is lengthy and costly, often longer than a decade from laboratory to consumer availability, involving extended clinical trials, and perhaps necessitating hundreds of $millions in investment. As we’ve seen, however, FDA re-makes federal rules with respect to pet foods. In September of 2012, the FDA announced yet another (Draft) Compliance Policy: “Labeling and Marketing of Nutritional Products Intended for Use to Diagnose, Cure, Mitigate, Treat or Prevent Disease in Dogs and Cats” which creates an exception to these legal requirements if the food is sold by or purchased pursuant to veterinary transactions:

Draft Compliance Policy Guide § 690.150

Labeling and Marketing of Nutritional Products Intended for Use To Diagnose, Cure, Mitigate, Treat, or Prevent Disease in Dogs and Cats.

“FDA does not generally intend to recommend or initiate regulatory actions against dog and cat food products that are labeled and/or marketed as intended for use to diagnose, cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent diseases... when all the following factors are present. Specifically:

(1) Manufacturers make the products available to the public only through licensed veterinarians or through retail or Internet sales to individuals purchasing the product under the direction of a veterinarian;

(2) manufacturers do not market such products as alternatives to approved

new animal drugs;

(3) the manufacturer is registered under section 415 of the FD&C Act (21 U.S.C. 350(d));

(4) manufacturers comply with all food labeling requirements for such products (see 21 CFR part 501);

(5) manufacturers do not include indications for a disease claim (e.g., obesity, renal failure)

on the label of such products;

(6) manufacturers limit distribution of material with any disease claims for such products only to veterinary professionals;

(7) manufacturers secure electronic resources for the dissemination of labeling information and promotional materials such that they are available only to veterinary professionals;

(8) manufacturers include only ingredients that are general regarded as safe (GRAS) ingredients, approved food additives, or feed ingredients defined in the 2012 Official Publication of the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) for the intended uses in such products; and

(9) the label and labeling for such products are not false and misleading in other respects.”

The consequence is that the FDA, through Compliance Policy, will now allow

pet foods

to be drugs.

Bypassing extensive clinical trials, pet foods can now diagnose, cure, mitigate, treat or prevent disease; (“Pet foods...the only FDA approved non-drug,” observes Thixton). As drugs, these pet foods are to be sold only through doctors (veterinarians) and it is only they who are provided marketing information: not the consumer.

Incorporating other FDA CPG rules, these “prescription” foods can legally be sourced from inferior, “filthy,” diseased, or contaminated waste ingredients. Further, it will not be required that these “prescription” pet foods be labeled to state actual protein, carbohydrate or fat contents; nor will they be required to state where or even what country these ingredients are sourced from.

Compliance Policy for “Additives,”

because: regulation takes too long

Provisions for pre-clearance for pet food additives are defined in Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR 571) subchapter on animal drugs, feeds, and related products. But FDA’s CVM does not scrutinize manufacturer practices with regard to pet food additives because it is too “time consuming.” As described in the “Program Policy and Procedures Manual” Guide 1240.3310:

“CVM has used regulatory discretion and not required food additive petitions for substances that do not raise any known safety concerns. In this case, we ask the company to submit the information needed to list the ingredient in the Official Publication of the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO). This ingredient definition process is done to conserve agency resources, as food additive approval is time-consuming. CVM reviews the data to ensure the ingredient has utility and can be manufactured consistently to meet product specifications. Although ingredients used under regulatory discretion are still unapproved food additives, we agree we will not take regulatory action as long as the labeling is consistent with the accepted intended use, the labeling or advertising does not make drug claims, and new data are not received that raise questions concerning safety or suitability.”

FDA policy creates process for industry self regulation

As a result, companies are not required to notify FDA before they use a chemical additive in pet food, but merely inform the voluntary AAFCO organization. CVM does, however, work to ensure that an ingredient has “utility,” presumably a term defined by the manufacturer. In such absence of government oversight, consumers must accept that the safety of pet food products is nearly entirely within the purview of the manufacturers themselves.

In the end, the only requirement that the industry must meet is to adhere to the Labeling Act, which states that food must contain the name and address of the producing company, whether the product is intended for dogs or cats, the weight of the food, and the guaranteed analysis. Even these meager standards are not, however, meaningful, since most pet food is made under contract arrangement by co-packers: and so the “manufacturer” is not information that is available to the consumer.

ENDNOTES

[1] Watchdog journalism: prior to World War I, “muckraker” referred to a writer who investigates and publishes truthful reports to perform an auditing or watchdog function. Today, the term describes a journalist writing in the adversarial or a non-journalist whose purpose in publication is to advocate reform and change.

[2] The US Dept. of State endorsed the Brent recommendations, and in 1906 President Theodore Roosevelt called an international conference, the International Opium Commission, (Shangai: 1909). A second conference was held at The Hague (Holland) in 1911, through which the first international drug control treaty emerged, the International Opium Convention of 1912.

[3] The use of DEG for economically motivated adulteration of consumer products has resulted in numerous epidemics of poisoning since the early 20th century. In 2017 and 2018, malicious fraud of this type has focused on pentobarbital appearing in pet foods.

[4] “Active” vs. “Inert” Ingredients: active ingredient(s) must be listed on the label (percentage by weight), while inactive or “inert” ingredients do not. Federal regulations allow manufacturers confidentiality on issues they claim would otherwise make them vulnerable to market competition. As such, “inert” ingredients became protected by federal law as trade secrets. Trade secrets protect commerce by preserving an advantage over a marketplace competitor or the public.

While the word “inert” suggests benign effect (and likely connotes safety to the consumer), this is misleading, because these undisclosed ingredients are neither biologically, chemically, nor toxicologically inactive. Legally, “inert” merely means those substances are not the “active” ingredient. In actuality, many “inert” ingredients are as toxic, or more toxic, than the registered “active” ingredients (see: Fleas & Ticks).

[5] Among the important FDAAA changes:

increase in product, establishment and application fees, including a voluntary user fee program for direct-to-consumer (DTC) television advertisements;

FDA now held authority to require post-market clinical trials to assess or identify a serious risk with a drug product, including authority to direct re-labeling, and authority to impose distribution and use restrictions, such as limiting distribution of a drug to certain facilities (example: hospitals), under a new process called a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy;

requiring companies to submit DTC television advertisements prior to air, including requirements for clear and conspicuous safety information;

established civil money penalties;

limited pediatric exclusivity;

expanded requirements for clinical trials and expanded the clinical trial registry and results databank.

[6] Profit-driven desperation to bring these animals to the slaughterhouse door and into the human foodchain is so intense, that horses and cattle that are sick and near death (unable to stand or walk: the “downers”) are commonly tortured to get them to rise or keep moving, so that they can be butchered. Notorious recent examples include the pain and misery inflicted on cattle at the Hallmark Meat Packing Co., (Chino, CA: 2008) and the Central Valley Meat Co. (Hanford, CA: 2012) both major beef suppliers to America's school lunch program. Workers filmed kicking, whipping, dragging, water-spraying (so that they could be repeatedly electro-shocked) the animals also appear comfortable as these “non-ambulatory” cattle are gouged and throttled into the kill chutes with forklifts (where it often takes several attempts to kill them); and in the latter case, apparently while US Dept. of Agriculture

inspectors were on-site.

According to a voice-over on the tape provided by Compassion Over Killing of the Central Valley plant, “countless deaths we documented were slow and agonizing. Rather than properly stunning animals, Central Valley sends cows who are still thrashing after they've been shocked down a conveyor belt where they are hoisted kicking and struggling (by one leg) before their throats are eventually slit.” According to DawnWatch “one segment showed a cow who was still alive after being shot in the head being suffocated by workers who stood on its mouth and nostrils. Another featured downed cows, unable to walk, who were shot in the head as many as four times, with workers often walking away as the animal continued to struggle and kick...” The American Veterinary Medical Association labeled the abuse “indefensible and deplorable,” questioned the food safety risks associated with that handling, and urged the US Department of Agriculture to investigate whether USDA-FSIS inspectors at the facility were providing

adequate oversight.

But even beforehand, these unfortunate animals are pumped with synthetic growth hormones and antibiotic drugs (arsenic, erythromycin, penicillin, procaine, streptomycin and, trimethoprim are examples) to combat the effects of stressful, overcrowded, and dirty conditions of factory farming, as well as inferior and unsanitary food they themselves are fed.

"institutionalized animal abuse"

Factory farming is the industrial farming processes of raising livestock in confinement at high stocking density, where a farm operates as a factory. Confinement at high stocking density is one part of a systematic effort to produce the maximum output at the lowest cost by relying on economies of scale, modern machinery, biotechnologies,

and global supply trade metrics.

By nature, the crowded living conditions spread of disease and pestilence, and necessitate mitigation through continuous administration of antibiotics and pesticides—which then become part of the food chain. Antibiotics and growth hormones are additionally used to stimulate livestock growth. Food is supplied to livestock in place, and physical restraints are used to control movement or actions regarded as undesirable: called Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFO).

Animals living in these conditions are often mutilated to prevent them from harming each other or becoming cannibalistic in reacting to the lack of space and psychological stress of the environment. The large concentration of animals, their pain and anguish, animal waste, and the potential for close exposure to dead animals poses ethical issues, and these techniques to sustain intense profit objectives are, while often culturally accepted as “necessary evils,” are rightly identified as institutionalized animal abuse. Pollution and destruction of biodiversity are additionally cited as environmental concerns of these

modern agribusiness practices.

[7] Renderers convert dead animals and animal parts that otherwise would require disposal (garbage)

into a variety of materials, including edible and inedible tallow and lard and proteins such as

meat and bone meal (MBM).

Rendering (boiling) separates fat (used as an ingredient elsewhere), removes water, and kills bacteria, viruses, parasites, and other organisms. However, the high temperatures used (270 - 300°) can alter (denature) or destroy natural enzymes and proteins found in the raw ingredients, which can contribute to food intolerances and allergies, and inflammatory bowel disease. In order to maintain nutrient profiles, pet food manufacturers must replace these nutrients synthetically. These problems are more common with dry foods, because the ingredients are cooked twice: first during rendering, and again in the extruder; and, the baking process —perhaps 500° —can further stimulate the formation of carcinogenic (cancer causing) compounds. Rendering does not destroy certain chemical contaminants, such as the euthanizing drug pentobarbital, emerging as a major scandal in 2018. (See: The Nutrition Connection: What's Really in Dog Food?).

[8] Fate of sodium pentobarbital in rendered products (O'Connor, Stowe, Robinson: University Of MN; Am. J. Vet. Res., Vol 46, No. 8, 1985).

[9] Susan Thixton writes: “I doubt that the CVM… (tested) dog foods for pentobarbital simply because a few veterinarians complained that (it) was losing its effectiveness,” (the stated reason for FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) to undertake the research). “My theory is that CVM… (was) under extensive pressure from the pet food industry, hoping to calm consumer panic that their pets might be consuming a food that contains a euthanized dog or cat.” CVM testing identified no species source of pentobarbital, but Thixton accurately criticizes that “on one hand the FDA/CVM tells us that pentobarbital discovered in dog food would originate in euthanized dogs, cats, or horses. (But) because CVM testing found no DNA they made the statement that no pets are rendered into pet food based on inconclusive testing. To date, there is no clinical evidence to refute suspicions, [photographs], hidden video, and personal accounts that euthanized dogs, cats, and… horses are rendered and become pet food ingredients.”

In her book, Thixton reprints a lengthy personal account from a rendering plant employee: the worker describes conditions and ingredients being processed that are so wretched, it becomes uncomfortable to read: so much so that we could not reprint it here, even with her permission.

“Clifford takes a seat on the floor next to David and his mother.

He finds an empty page at the back of the album

and inserts the photo.

As he does, he repeats my words:

”On the pages within are those who came before;

those who shared their lives with us all too briefly.

These are the lives we honor... beloved angels...

who have crossed over to the realms of light...”

…When the boy finishes, I no longer see David, Clifford, Sally, and Joshua as distinct entities.

Instead, they are one integrated whole… connected to form something new—

better than what they were before—in some ways that are measurable and some ways that are not.

The death of a little black dog has brought them all together. And before that, a chimpanzee named Cindy brought David and Jaycee together; and before that a horse named Arthur brought David and Sally together; and before that a kitten named Tiny Pete brought Sally and Joshua together; and before that a cat named Smokey brought me and Martha, and then Martha and David together…

And a lifetime ago, in the middle of a dark and nearly deserted road, a deer pleading for

a quick and painless death brought David and me together.

Jaycee had said that communication is merely the transfer of information in a way that has meaning to the recipient. It doesn’t need to be spoken in words or even said out loud; it just needs to mean something.

That deer in its last moments spoke to me and David just as clearly and just as deeply as Cindy spoke to me.

The language was different, but not the strength of the voice.

They all spoke to me. And they all spoke in a way that mattered—a way that moved and changed me.

Watching Sally, David, Clifford, and Joshua so willingly share their grief and love, the pieces finally do make sense. I’ve been so foolish, running through the forest searching for some profound and eclipsing life meaning when it is the trees themselves that were bejeweled the whole time: Skippy, Brutus, Arthur, Alice, Chippy, Bernie, Smokey, Prince, Collette, Charlie, Cindy, dozens of cats, dogs, and other creatures whom I treated, made better, eased into death… or simply had the privilege to know.

Each was worth in his or her own right of being valued, each instrumental in connecting us and then moving us onward in our own lives, and each gave much more than any of them got in return.

Clifford was right: each one mattered. I was better for knowing any of them and blessed

to have known all of them. I think I helped, but I know with certainty that I cared. I am not empty handed.

I cared. That is meaning enough.

I was correct about what was waiting for me.

Those creatures I’d been afraid to face in death actually were there in the end. All of them.

They looked into my heart with grace, mercy, and dignity and then lifted the weight I’d so long carried there.

They were more forgiving of my humanness than you can imagine.”

—Neil Abramson: Unsaid

N.B.: This essay is written for informational purposes. Our goal is to build awareness of concepts and define common terminology to stimulate discussion. We draw your attention to issues and concepts that are or may be important to the subject at hand, but do not consider that our interpretation is necessarily complete. Links are in blue & will illuminate when you pass your mouse over them. Nothing in this page is intended to be interpreted as advice or endorsement of any product. Any person who intends to rely upon or use the information contained herein in any way is solely responsible for independently verifying the information and obtaining independent expert advice if needed.